For the past two years, I have had the opportunity to design, test, and prototype an autonomous microbioreactor for my mechanical engineering capstone. The culmination of my five years at the University of Florida, this machine was commissioned by the UF Biofoundry Lab and was created entirely by a team of students.

The Premise

Our class was tasked with creating a machine for a biology lab that would combine the capabilities of many already-existing machines into one compact, economical, and sustainable design that could be added to and maintained over the years. Some of the main customer requirements were as follows:

Liquid handling capabilities, such as pipetting various volumes/flow rates

Waste management for liquid and pipette tips

Heating and cooling system

Gas exchange system for multiple gases

Photometric sensing capabilities

Shaking capabilities (linear, orbital, double orbital patterns)

Small benchtop footprint

User-friendly display interface

Adaptable, modular design

Less than $10,000 to manufacture

Although the full customer requirement list was over 100 items long, these were the main talking points. Now, to the design phase!

Phase 1: Design Iteration

For the first semester of the year-long project, my initial team was tasked with creating a singular design proposal that hit all of the aforementioned design requirements from the customer. This process was incredibly iterative.

First, my team researched the current technology on the market, including off-the-shelf components such as shakers and pipettors. (After all, why manufacture a crappy part in your student shop when you can just buy a non-crappy part?) We broke the customer requirements down into a few different subsystems: gas control, display, heating and cooling, sensing, liquid handling, shaking/gantry, and enclosure. From here, each of my team members was tasked with coming up with a few designs for each subsystem; we ended up with around 50 initial subsystem designs total.

I was in charge of creating the drawings for these initial designs; I have included some of them below.

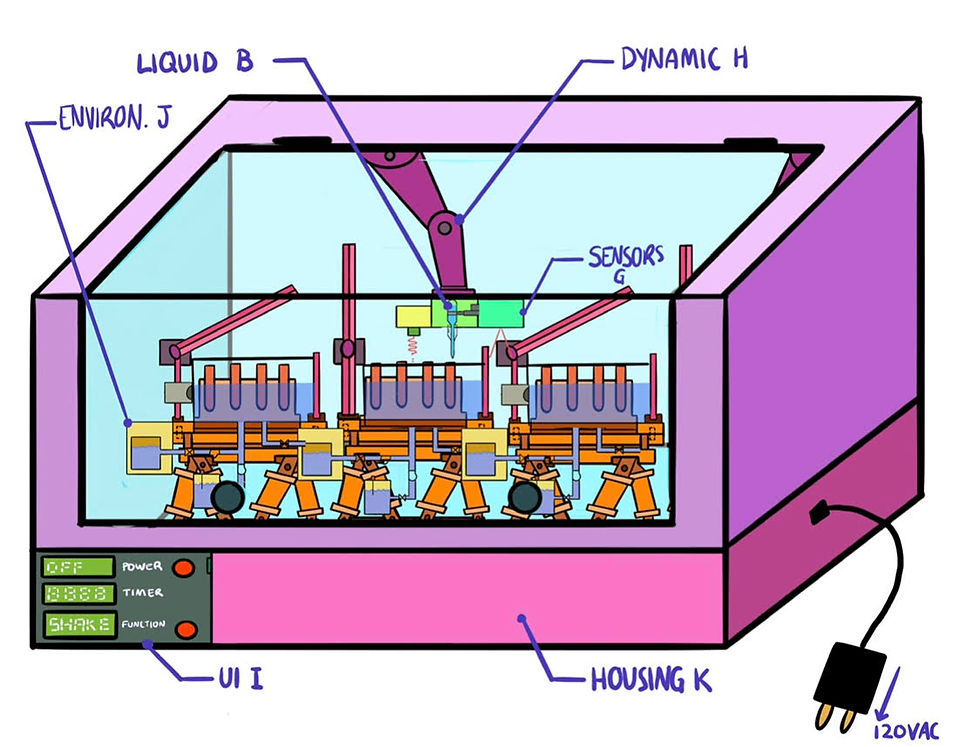

Next, using our initial subsystem concepts and a design matrix weighting system, we chose the best designs for each subsystem, later verifying feasibility and creating a few alternative combinations. Our initial combined design is shown below.

We continued to research and iterate our design with the help of our professors, ending up with a fully 3D modeled version for our final presentation. We also analyzed our design using finite element modeling and the NASA Technology Readiness Level system. Our final design proposal is shown below; I also created the final render and the branding.

Up next: putting our designs to the test!

Phase 2: Testing

For the next semester, two other classes had a go at designing and prototyping the bioreactor, starting with my cohort's initial designs for inspiration. A year after my team's initial design was proposed, I was back on the project. Within the last semester, a single initial prototype had been constructed, but it was very ugly, full of holes, and completely nonfunctional.

I was assigned to the Enclosure subgroup. Our task was to redesign, test, and prototype the bioreactor's entire enclosure, or housing, system, focusing on fit & finish and thermal handling.

First, to validate the design's material selection, we designed and conducted a few experiments based off of ASTM and ASHRAE testing standards. These tests primarily included thermal resistivity testing, infiltration testing, and emissivity testing.

Once the material selection was validated or changed according to our test results, it was up to us to create a working prototype.

Phase 3: Prototyping

The final phase of our capstone design was to create a working prototype of the enclosure subsystem. Some changes we made to the initial prototype were as follows:

Sheet metal redesigned to fall within our manufacturing capabilities/tolerances (no more right angle bends).

Sheet metal bends substituted with flat sheets welded into OTS angle brackets.

Insulation changed from styrofoam (extruded polyurethane) to expanding polyurethane pour foam (better adhesion, stiffness, and thermal resistance).

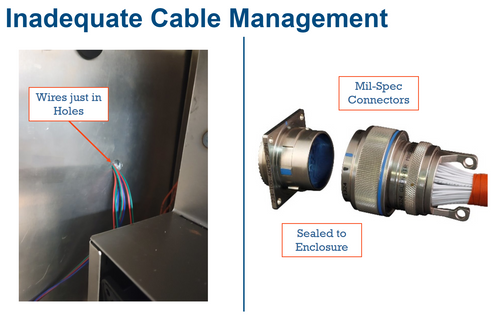

Wiring now fed through enclosure walls using MILSPEC connectors (previously were just stuck through a hole).

Rivets better designed using engineering standards. Welding implemented when possible.

Window on door now sealed into door with custom designed 3D-printed PLA shell.

Door hinges changed for better fit to combat door sag.

Door latch changed to more ergonomic design for ease of use.

Door seal changed to have complete contact with enclosure interior interface.

Enclosure designed for easy modular assembly.

Some photos of our final design and prototype are included below.

Takeaways

Overall, this project was incredibly rewarding. I learned how to work in a team for a large scale engineering project, how to design iteratively, how to create a working prototype, and, most importantly, how to trust myself as a designer. I am excited to see a working model being used by future UF biologists and to know that I created something that made their lives easier.

Thank you so much to my team mates, the UF Biofoundry Lab, and my instructors, Dr. Matthew Traum, Dr. Sean Niemi, and Noel Thomas; for the opportunity!

Comments